In recent summers we have take a series of summer holidays walking in the Yorkshire Dales – first in Swaledale (staying at Low Row near Reeth), then in Wharfedale (based in Ilkley) and last year in ‘Bronte Country’ near Haworth. In each case we combined our week in Yorkshire with a day or two staying somewhere en route to and from our home in Plymouth, or in one case a second week away in Norfolk and Suffolk. For a change, this year, we decided that we’d like to spread our holiday time out over the summer months, and so we picked a couple of fairly local destinations for ‘long weekend’ walking holidays and also booked five days over in Suffolk, combining this with a visit to elderly relatives and an old university friend on mine.

The first of our summer 2025 mini-break locations, in June, took us back to the very familiar territory (for me at least) of the Quantock Hills and the Somerset coast. I grew up a short distance from there in Bridgwater, and we would frequently go on family outings to the area. I also spent quite a lot of time at an activity centre in Kilve on short courses of various kinds (mostly musical).

Although I do like discovering new places, I also very much enjoy returning to familiar haunts, especially for a short trip when you want to be able to slot straight into holiday mode without having to spend time orienting yourself and getting the lie of the land. Our Somerset trip – staying in an AirBnB Shepherd’s Hut near the village of Crowcombe, tucked at the bottom of the western side of the Quantock Hills ridge, very much fell into this ‘familiar territory’ category.

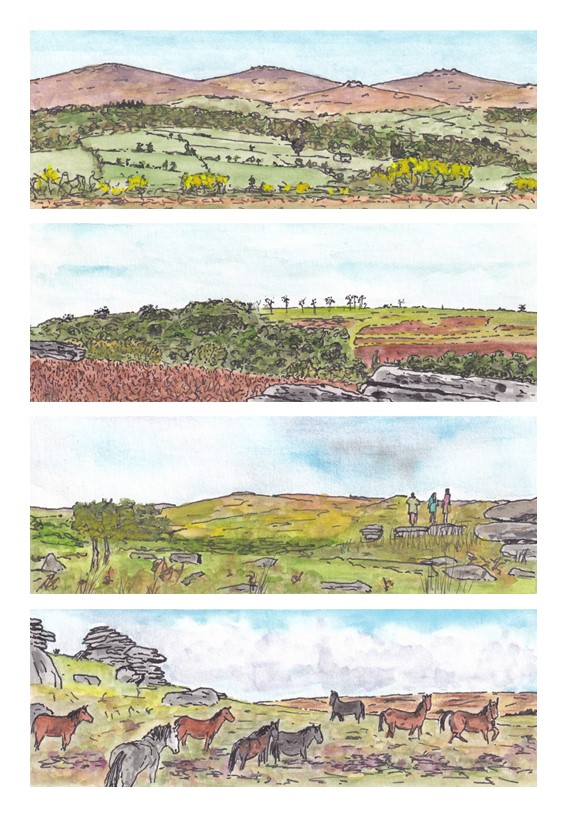

While we were away we enjoyed completing a couple of lengthy walks direct from our accommodation (I particular enjoy a stay away that doesn’t involve having to get in the car), and I was able to spend quite a bit of time painting. In this post I’ll feature four of the pictures that I produced during the break, and I’ll pick up the thread with another post soon that will feature a further group of five pictures.

We started our holiday with lunch at a favourite cafe, the Driftwood Cafe at Blue Anchor – the subject of my first picture (shown at the top of this post). It’s not a fancy cafe at all – I’d describe it as a ham, egg and chips or baked potato cafe – it’s just a nice, simple, easy-going place for a quick bite to eat.

Suitably refueled we then drove the short distance to Kilve and did a short walk (~3 miles) along the coast to East Quantoxhead, before turning inland and returning to the car, with a stop at the Chantry Tea Garden at Kilve where we were the only customers and had an interesting conversation with the owner, who used to be a frequent visitor to Plymouth. The two pictures below show a view of a field that we passed on the return leg (I’ve got a thing for trees silhouetted on the horizon) and the view that we had from our table in the cafe garden of The Chantry itself and the white cottage from which the cafe was run.

Finally, for now, here’s a scene I painted of the view looking west in the direction of Exmoor from the base of the Quantock Hills. I’ve tried to capture the way that there are successive ‘layers’ of rolling hills as the eye moves towards the horizon, each becoming progressively just a little higher than the previous one. Although wild landscapes can be exhilarating, I do like a farmed landscape – a patchwork of fields, hedges, copses and the odd farm building.

All of these pictures were really just quick ‘practice’ pieces, but I like them all in different ways – Driftwood Cafe for its small details, the grass-cut field for its slightly abstract form, Chantry Tea Garden for its looseness, and Somerset Fields for the way it captures something of the wide expansiveness of the view.

If you have a favourite of these four pictures write a quick comment to let me know!