I read James Nestor’s book Deep back in February/March, but I am a bit behind with my efforts to write blog entries and so I am only just getting round to writing something about it now. You could say that I have been submerged to such an extent that I have not been able to see even a glimmer of light to guide me in the right direction to get back on track…

Deep was not a book that I had ever noticed and thought I wanted to read, but one morning, at the back-end of last year, one of the students I teach in my first-year introductory oceanography module (there are almost 300 of them, although they are rarely [never?] all to be seen in the same place) came to see me during the break in one of my lectures and passed their copy of the book to me suggesting that I might like to read it. I think that my students generally assume that I am fascinated by the subjects that I teach and will love finding out more about any topic relating to them. This is actually not the case – it was a fairly random and somewhat inexplicable sequence of events that ended with me studying for an MSc and then a PhD relating to oceanography, and from there it was just a case of me continuing to follow what seemed to be the simplest path (i.e. the one that involved me making the minimum number of decisions) into my career as a Marine Science lecturer. Inexplicable it may have been (to me at least), but it’s a path that stuck, such that here I am, some 33 years later, still following it (maybe some would call it a rut!). So, in fact, I am not that interested in the undersea world, marine life and topics such as diving, I just somehow create the impression that I am fascinated by the oceans when I am teaching students about the various processes that occur within and on them.

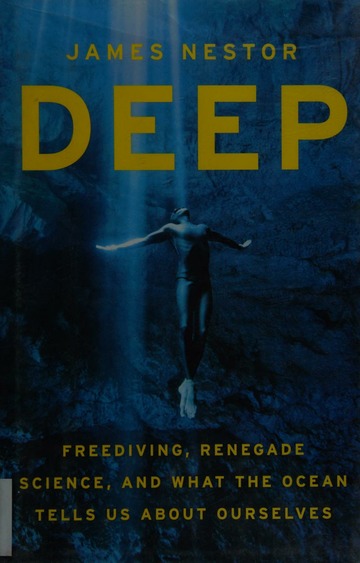

Nevertheless, I thanked the student for passing the book to me and set it aside to read at some point. I had previously read his later book ‘Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art’, I knew that Nestor wrote well and would almost certainly have some interesting points to make, so it wasn’t really a difficult decision.

Deep is mostly about the pursuits of the very strange (to me at least) group of humans who strive to head as far as possible downwards into the ocean depths. It is nearly structured as a series of chapters titled by a depth in feet (e.g. -650, -2500, -35,850) and containing stories of human exploration towards that depth. Initially, at shallower depths, Nestor describes the pursuits of free divers, including the absolutely insane group of people that risk death competing to dive deeper and longer than their rivals. Some of the events that Nestor recounts, in which competitors emerge from the water with blood streaming from their faces, or in a semi or fully unconscious state were pretty horrific and I find it surprising that i) the ‘sport’ is allowed to continue, ii) anyone wants to participate in it and iii) Nestor still went ahead and learned to free dive so that he could join in with various activities.

In the latter part of the book, much of the content focuses on scientists and researchers who combine diving with attempts to better understand the behaviour of marine life such as various types of sharks and whales. All of this content was quite interesting, even for someone who is not at all obsessed with sharks and whales like me! It was particularly interesting to get a glimpse of the kinds of private organisations and collections of individuals that operate in this area of scientific exploration and research – often rather cavalier and unorthodox in their approach, because, I suspect, anyone trying to do the kind of ‘animal-encounters-at-close-quarters’ research that the book describes in a traditional, more highly regulated, academic setting would probably find that their efforts were thwarted by the requirements of such niggly things as risk assessments and ethical considerations.

In the end, I enjoyed reading Deep, and found it interesting to get a glimpse of the world of underwater activity it describes. However, it did nothing to make me wish that I was able to descend below the waves myself, quite the reverse in fact. I’ve always been quite happy existing on the solid substance of the land surface, and it’s pretty obvious to me that nothing is going to change that now!